Chapter 4

…

The evening shadow of the

guava tree was falling on the bamboo gate. “Please have a seat here, Anna.”

Ratnavel picked a brick and sat on it as he called out to Rasokkiyam while

taking out his shaving kit from his armpit. His frame looked frail, yet he was

capable of drinking a mug full of arrack in one gulp and keeping the mug down

without any sound. The only good habit he cherished in his profession—if he was

drunk, he would never touch his shaving razor.

Ratnavelu immensely respected

Rasokkiyam. There were many in the village who, out of frustration when they

couldn’t find any good barber, were critical of his work and would pass

derisive remarks behind his back: “Go to him. He is very skilled in giving you

a smooth shave.” But Rasokkiyam had never judged him for his work. He had never

attempted to demean Ratnavel’s work by telling him to try his hand on his face

while leaving for another village to attend a funeral. Rasokkiyam was so

indifferent to his stubble that he wouldn’t shave it for days, as he believed

that the hair would prove of no worth when the humans as such were indolent. He used to get his stubble

shaved off only when Ratnavelu would chance on the way, extending his service

with an assurance, “Anna, I’d come to your house.” If it failed to happen, it

was Panjalai who would make it happen with her shouts, the way she did that

morning. “Hey… Ratnam, you won’t lose anything if you spare a minute to shave

his stubble off. Will you? See how horrible he looks, like a rabbit hunter with

his thick beard.”

Rasokkiyam took off his dhoti

from his shoulder, kept it on the stone mortar, pulled a wooden stool lying

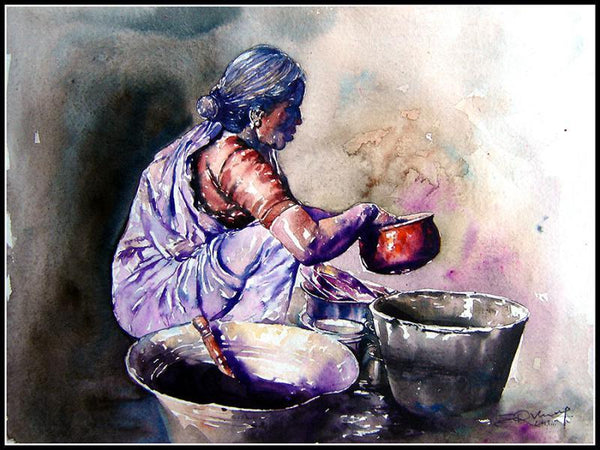

near the hut, and sat on it. Panajalai was washing the utensil to boil the

rice. A sharp pain radiated for a second in her waist the moment she stood up

after washing the utensil, causing her face to wrinkle a moment before she

slowly became normal. She tilted the can to pour the water into the utensil.

Beyond the fence, Ambujatchi

was blowing air into the stove she had lit under the shade of a tree. Any

innocent question thrown at her to know where Kanagaraju had gone would invite

an unsympathetic reply from her: “You are asking me this question as if he is

such a nice chap who would tell me everything before he goes somewhere.”

Kanagaraju would be busy on Wednesdays at the Viruthachalam market. On Fridays,

Madapattu market. On Saturdays, Chettyanthangal market. He would be busy all

day in these markets. He was skillful in assessing the profit and loss in his

business with the mere moves of his fingers under the towel. Working in the

fields and looking after his family chores did actually play a secondary role

in his life.

Ratnavel scooped up a handful

of water from the brass bowl and rubbed it gently over Rasokkiyam’s face.

Softly rubbing his back with the back of his hand to remove the ants crawling

on there, Rasokkiyam remarked sulkily, “Water hasn’t been filled yet in those

two canals in the groundnut field. I thought of doing it in the evening when

the sun gets less harsh. But you have caught me and made me sit here as if I am

leaving to find a girl for me.”

“You had better find someone

like that. Let those canals remain unfilled for some time. You can do it in the

morning when the dews fall” Panajalai said as she was lighting the stove.

“What my akka says is

correct, Ratnam. She is also physically drained these days. Even if she could

manage her days with a simple porridge at home, the lady coming to this house

would take care of the fields and family chores.” Ambujatchi, sitting beyond

the fence, commented with a smile.

“You are right. We have to

find a girl for my thambi to get him married to her as you wished. He isn’t

a worthless drunkard. Is he?” Everyone turned their attention to this voice

that erupted suddenly. Ratnavel, who was shaving the stubble, also stopped his

work and looked around. Karivaratha Padachi was coming in through the gate. He

had come with a simple loincloth without his usual red soil-stained headscarf.

His body, with the streaks of red soil all over, resembled a pangolin that was

pulled out of its sand mound. His legs and hands were covered with the layer of

sand. A small leaf roll containing ‘nose powder’ was dangling from the thread

that ran around his waist. As his name suggested, he was a dark-complexioned

man and remarkably taller. Though his skin had begun to wilt due to age, his

voice still remained orotund.

If Kari Padachi walked on the street,

it would wear a cheerful look. “Hey lady… Your husband comes to me with a

complaint that the leaves in the bundle of weeds don’t have any leaves.”

The women around him would

also reply in a similarly lighter vein that matched his wits. “That man suffers

from a weak stalk. How would the leaf sit on a weak stem, Mama?”

Innocent boys would never be

able to escape his teasing words. Holding their penile area tightly, he would

tease them, “Do you know a cat and rat were wrestling last night at your home?

“I don’t know, Grandpa,” the

boys would reply innocently.

He wouldn’t leave them and

tease them more. “Go to your mother; tell her that the old man Kariyan was

asking about it. Go…run to your mother.” Those innocent boys would inform their

mothers what Kariya Padachi had told them, which, in turn, would force those

women to blush with shyness and rebuke Kariya Padachi, obviously faking their

anger. “Mama, you have nothing to do other than this?” They would reproach him.

Karaiya Padachi, though known for such innuendos, was a man of different stuff.

If he happened to witness street scuffles, he would be the first person, just

like Rasokkiyam, to jump into the scene to mediate between the parties to go

amiably. “Leave this petty matter. These women are toiling every day in the

fields and looking after the families. It is natural that they tend to get

annoyed at petty provocations. It is we who, supposed to be responsible, must

bear with them without getting angry,” he would say.

“Mama, find a very good girl

for him. Please make it sure that my aunt Muthukannu also accompanies you when

you go to find a girl. She is very skilful in finding a girl who is perfectly fit

in all ten matching elements” Panjalai remarked with a smile.

The moment he heard the name

of Muthukannu, all his enthusiasm and high-spirited mood took a beat, forcing

him to sound a little dull. “Why are you throwing me into a furnace? That old

corpse will cut me into pieces and take the dung out of me.” He took out a

pinch of nose powder from the leaf roll and sniffed it once.

Muthukannu was very much

attached to her husband, Kariyar, probably because they did not have children.

She never preferred a second to leave him alone. She would become restless if

she couldn’t see him around even for half an hour. She would then stop everyone

on her way, posing them a repeated question: “Did you see that old fellow?”

They owned no land, except a house. They just depended on a pair of bullocks

and a cart for their sustenance. At times, he would go for ploughing or

carrying sand for wages. He would do menial work for wages whenever he couldn’t

find jobs to use his bullock cart.

“If your teasing and overtones

remain unbridled even in the presence of such an aunt, what would have happened

if you had gotten a woman who cares for you little?” Ambujatchi said as she was

carrying the vessel with boiling stew.

“Leave her aside. What is the

matter, Anna?” Rasokkiyam asked him, wiping off his buttocks to get rid of the

ants.

“Our Kanakkan Chetty has

dismantled his hut and started building a brick house. I went there to dig a

hole to plant the ‘kadaikaal.’ On the western side, the surface is hard.

Hardly had he completed his words, Rasokkiyam gently pushed Ratnavel’s

razor-wielding hand aside, grew curious, and asked, “What are you telling Anna?

Almost everyone in the village is living in their houses without even getting

it partitioned with dried leaves and keeping their roof as leaky as a broad

beans trellis with holes, fearing the Neyveli men who would take away their

land anytime. Here, you are telling someone is digging a hole for planting a

kadaikaal.”

“This is what everyone who had

gone there to see is asking. The super confident Chetty is ready with a reply

that it is a matter of concern only when it actually happens.” Telling this,

Kariyar said, “Give me your crowbar. My crowbar has become blunt due to its use

since morning.”

Ambijatchi, hearing his words,

passed a witty remark from that side: "Muthukannu aunt complained about

you yesterday.”

“Complaint? What complaint?”

Kariya Padachi asked her, with a tinge of suspicion.

Trying to control her

laughter, she said, “Your crowbar has become fully blunt like this

crowbar. No use of it anymore.

“May I leave the moustache a

little thin?” - Ratnavel’s usual words of endearment every time he shaved his

stubble. Rasokkiyam replied as usual, “If only I had a moustache, people would

come to know that I am a family man. Wouldn’t they?” Knowing that this would be

Rasokkiyam’s reply, Ratnavel had already shaved off the right side of his

moustache.

“Aththai…” Panjalai and

Rasokkiyam, without turning their heads, just rolled their eyes towards the

doorway facing the street from where the voice came. It was Devaki, Vadivelu’s

wife. Getting no reply from inside, Devaki crossed the veranda and walked in.

She came straight to where

Rasokkiyam was getting his shave and started placing her grievances. “Mama, do

you know about the scene that happened yesterday? You can get it confirmed with

Aththai if you like. He is scolding me as if he had never come across a dirty

dog. Let me be a piece of shit, not even worth holding a quarter of an acre.

Let him be a big landholder owning a lot of land. But he has no right to push

me away from the house by my neck. Even if I go out of the house, will my

brothers deny me entry into their house?”

A worn-out sari had been

wrapped around her well-toned body, obviously to offer it a poverty-stricken

look. An unfriendly countenance due to persistent scuffles at family. She kept

adding up her grievances against Vadivelu.

Vadivelu, son of Pakkiri

Padaiyachi, owned more than ten acres of land. Though he lost his mother when

he was very young and was brought up by his father, he remained a responsible

man without getting into unnecessary brawls. Devaki, who hailed from the nearby

Vellur village in the south, came there for weeding. As she was looking

beautiful in her youth, Vadivel fell for her and started speaking to her

lovingly. Their talk that grew slowly had later become an inevitable passion in

their life. She then brought people herself for weeding and began looking after

the harvest. Later, she became the owner of that ten acres of land. It had been

nearly ten years since the day she became the owner of the land. Not a single

day, since her arrival, was left without a quarrel between the couple. Despite

these quarrels, she could, somehow, become a mother of two children. By no

means could she be rated an ordinary soul. A simple existence with her weeding

spade was the life she was actually leading until the day she stepped into that

house. After that, everything changed. Her complaints about the hot sun and

itchy coarseness of grains did drive Vadivelu nuts. All his efforts to forget

his inexcusable mistakes of having brought a petty woman like her into his life

went in vain due to her frequent teasing, which would then result in him

furiously smacking her. ‘There must have been a good round of a show

yesterday.’ Rasokkiyam could guess what might have happened.

Panjalai, while letting the

water flow away from the utensils she had just washed, said, “You are not going

to take his advice earnestly to run your family. Are you? Your complaint is a

thousand and one times old. You had my ears burnt with it.”

“I haven’t come to you. You

have the habit of finding no mistake in his behaviour. You better mind your

business. I am speaking to Mama.” Devaki responded rudely and turned to

Rasokkiyam. He rose from his seat when Ratnavel made a brief sound, ‘mm,’ to

mark that he was done and told her brusquely without asking her the details of

complaints, “It is alright. Let me speak to Vadivelu about it in the evening.

Now you leave.”

“Mama, keep him informed about

what I am up to. I just worry about my two children, who would be standing on

the street if I am no more. Or else…” As soon as Devaki left after spewing out

her words, Panjalai, standing in the veranda, let out a thick thrust of

contempt. ‘Mkkkmm.’ Devaki opened the gate amidst that broken sound of contempt

and strode out with a murmur: “If those Neyveli men, who keep everyone on

hooks, take steps to acquire the lands immediately, things will be set right in

a day. Only when those men snatch away all his ten acres of land from him the

way the tooth is extracted, he would understand where he actually stands. Till

then, I need to keep coming to them with complaints and get insulted

repeatedly.”

***

Hardly had she been aware how

fast she hung her school bag on the nail on the wall, Bhooma paced fast to the

entrance and asked her mother, “Can I get the rice now?” With the same urgency,

Vairam, Thangam, and Kasappu were holding their plates in their hands, vying

with each other, demanding rice at Ambujatchi’s house.

Panjalai was grossly annoyed

at seeing her. “You useless girl! You are an adolescent girl. It is expected of

you to wash your hands and legs, change your dress, and clean up the house

after coming from the school. But you stand here demanding rice to eat. It

seems that you were thinking of only rice in the school. Hell with your

studies.”

Unable to bear her harsh

words, Ratnavel said to her as he was packing his shaving kit, “Periyayi,

why are you throwing such harsh words at this hungry child? If it is available,

ask her to serve herself. If not, just tell her to wait till it is made.”

“I have a handful of rice. I

thought of giving it to you and your wife, Muthal. Now I will give it to this

girl, and you may leave empty-handed. Will I be bothered with it or what?”

Panajalai remarked as if she was speaking to her enemy.

Ratnavel stood aghast at what

Panjalai had told. “Oh…no…give it to me. She is such a young girl. She can go

hungry for some while. Muthal would be eagerly awaiting something from me if

she knew where I had gone to work.”

“Akka, look here. If it got to

evening, Periyamma would start her rants like this” Thangam extended her hand

with a plate of rice from the other side of the fence. Bhooma received the

plate, scooped a morsel of hot cooked rice from it, stuffed it into her mouth,

and sat on the doorway.

“Can’t you wait a little till

it turns cold? You are swallowing it as if you had never seen rice.” Letting

her rants go in one ear and out the other, Bhooma was busy eating as though

proving hunger blunts the taste buds.

Wagging its tail, the

‘naughty’ came near to her and stood by her legs. His eyes were filled with

craving. This dog came to her as a newborn puppy without even its eyes opened

when she was studying in fifth grade. Since that day, it had become her dearest

companion. Wagging its tail, it used to be in her company every time brushing

her legs. She took out a handful of rice and placed it down on a stone.

Ratnavel collected the trimmed

hair strewn around on the floor, threw it away over the fence, and asked

Rasokkiyam, “Anna, what about planting seedlings?”

“How can I brave it? The water

in the wells keeps disappearing every time the Neyveli fellows move south. Even

if I am ready to dig a bore well, this uncertainty is forcing me to postpone it

like other villagers. What will I do if those Neyveli men suddenly appear in

front of me and order me to get out of my land? He got up, heaving a sigh, as

his voice grew thin. “I am planning to plant the seedlings tomorrow in a

quarter acre of land just to meet the needs of family.”

“Don’t be bothered. Who has

told you all these, Anna? I understand that the mines are not planned for this

side, the Kammapuram area. It will be opened in the east and west Melur and

Vanalavaram. You better pay your attention to digging a bore well rather than

getting unduly worried about all these.” Ratnavel exuded confidence that he was

good at international news despite being a simple worker in the village.

Rasokkiyam too felt that there must be some elements of truth in what Ratnavelu

had told. The lands around South Melur, lying in the east, and Vanathirayapuram

were lying barren after they were emptied of their residents. If the mining

project extended towards the east, leaving the south side, it would be for

everyone’s good. He prayed to the local deity Ayyanar and left for washing his

face.

Holding the bowl that Panjalai

gave him, Ratnavel bid her goodbye and opened the gate. Bhooma was throwing out

the water in the front yard after washing her plate.

“Are you going to your field?”

Bhooma turned, hearing Ratnavel’s voice.

“Yes, Ratnavelu.” Sikamani was

walking along the road beyond the fence. She plunged into an unbearable

happiness, and the sparrows that were tickling her for the last one week had

now started flapping their wings. As she felt that the same sparrows were flying

away from his eyes at the moment he turned his eyes towards her, she too sent

her sparrows back to him, making sure that no one watched her doing it.

***Ended***